Tattooing in Gaol

In 1845 the bricklayer, James Thirkettle, was sent to the solitary cell for a day for making marks on the back of his hand by pricking with a needle and ink. The Gaoler recorded only three occasions when he discovered prisoners pricking themselves in the nine years 1836-45 but tattooing was one of the illicit activities that went on in the cells, undetected. The Gaoler suspected it happened often enough for him to explicitly prohibit tattooing; as he noted in his daily log, eighteen-year-old James Thirkettle ‘had, as well as the whole of the Prisoners, been cautioned in that respect’.[i]

Tattooing – or marking or pricking as it was known before the late nineteenth century – was an amateur form of self-fashioning. It was not until the 1860s and 70s that professional tattooists began to set up in business, using standard designs or ‘flashes’.[ii] In the 1840s, then, tattooing was a popular art form, practiced among friends and workmates, especially in the military, sea-faring trades, and in gangs and criminal networks.

Serving a seaport, Yarmouth Gaol will have contained a higher proportion of tattooed inmates than most prisons. It is not clear how consistently the Gaoler recorded tattoo marks when he admitted prisoners but in 1839 he listed just under 20% of boys and men as being marked. Tattooing was much less common among female inmates; in 1839 only 5% appear to have been marked.[iii]

In gaol, tattooing was probably a communal activity more than a form of solitary occupation and distraction. Thomas Farrell, for instance, spent a day in the cells ‘for endeavouring to make some marks on the Boy Bowles’ arm by pricking it &c’.[iv] We do not know if this was the first time the boys, both fourteen years old, experimented with tattooing. But when Farrell returned a year later for his sixth imprisonment, his initials T.F. had been scored on his left arm, the T repeated on his left hand. By then he had served his first berth at sea when, most likely, he had proudly marked his initiation into life as a seaman with the anchor tattoo he was now sporting.[v]

In 1844 another group of boys were found by the Gaoler testing out tattooing methods, perhaps before trying it on their skin: ‘Stopped [Richard] Waite and [William] Jenkins potatoes for pricking letter H on [Henry] Barrett’s bread with piece of coal and a pin and stopped Barrett’s potatoes for permitting it to be done.’[vi] Needles and pins, used by male and female prisoners in sewing clothes, binding books, and repairing shoes, could be purloined for tattooing purposes. Indeed, during a previous imprisonment William Jenkins smuggled into his cell needles and a patchwork bag given to him by the prison visitor, Sarah Martin, to keep him quiet and useful. When the misappropriation was exposed by the turnkey, the boy tried to burn the bag and was insolent to the teacher, spending two days in solitary on bread and water for his outburst.[vii] Ink sourced from the prison classes could be used to dye prick marks, or alternatively soot that was ready to hand in the fires that warmed the dayrooms. Whether or not William had already practiced tattooing, he had found other subversive uses for soot, having spent three days in solitary for blacking one boy’s face.[viii]

From ‘Prison Heroines’ in Heroes of Britain in Peace and War by Edwin Hodder, late 1870s. Contrary to this image, Sarah Martin taught the sexes separately.

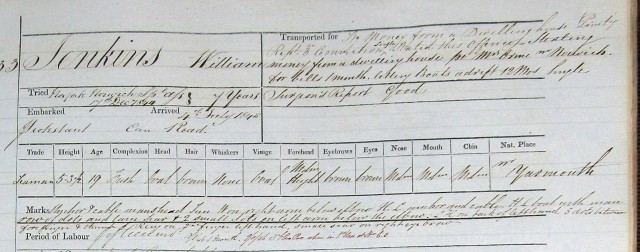

William Jenkins’s penal records and family history allow us to explore the significance of tattooing for boys and young men inside and outside gaol. Aged about fourteen when the tattooing experiment was interrupted, William was serving his third imprisonment. He was only twelve when first sentenced for a month in 1842 for stealing sundry tills and brass finger plates. According to the prison visitor, William had received no education and did not attend worship. She found him ‘Remarkably quick in natural ability and clever but refractory, fearless and illdisposed’ [sic].[ix] His restless behaviour is unsurprising given his recent past.

William had met the prison visitor before he came to gaol. In 1839 his elder brother Abraham served three months for stealing rope from a ship. In this short time Abraham learned to read and write under Sarah Martin’s tuition.[x] After his release the teacher continued visiting Abraham in his home, having strong hopes for his future ‘good character’ but fearing ‘his parents will not exercise a good influence over him’.[xi] She revised her opinion of the boy’s father, however, and comforted him through illness. She was at Mr Jenkins’s bedside when he died, later writing a poem on ‘The Believer’s Death’. ‘This holy and good man was a Tinker’, she noted, ‘with a large family in the deepest poverty’.[xii]

When Mrs Jenkins applied to the parish for assistance for her family the poor law guardians sent the widow back to her native parish in Wales with her five children. The Jenkins soon made their way back to Yarmouth where Abraham found work as a fisherman and William, like many young lads, picked up occasional labouring jobs. But the family struggled with poverty. When William was imprisoned a second time for stealing a child’s coat, he was handed over to the parish relieving officer on discharge, being destitute.[xiii]

Powerless in the outside world, William asserted himself in gaol notching up a total of eighteen punishments, far more than most prisoners accumulated. His disciplinary offences were associated with boisterous spirits and staking his place in the inmate pecking order: singing, swearing and shouting, keeping prisoners awake at night, pushing other boys about. The Gaoler, too, felt the boy’s temper. Ordering William to take his night pan and go to his cell for being disrespectful, the boy shouted, ‘“you may take the tub yourself and be b—–d for I will not take it”’ and ‘put his face in mine and in a rough tone of voice mocked me’.[xiv]

For boys like William, tattooing was a way of marking their toughness. The three youngest prisoners tattooed on entry in 1839 were all fourteen years old. Most began with rudimentary forms of tattooing that required little skill. William Chapman simply had a ‘Pricked spot on right and left hand’; William Gibbs had his initials and five dots on his left arm.[xv]

Most likely William Jenkins began his tattoos with such dots which then, as now, probably signalled gang membership or time served. We cannot know if any were scored while he was in Yarmouth Gaol but on his arrival in Van Diemen’s Land as a convict exile in 1845, William’s tattoos included a row of dots on one arm and five dots between his forefinger and thumb. He had been sentenced to seven years transportation at the Norwich Assizes, aged about fifteen or sixteen, for his part in a house robbery with two other boys he knew from the prison, both of whom wore dots among their tattoos. One of these boys, Joshua Artis, had been imprisoned, aged ten, in 1839 for stealing rope from the Yarmouth lugger Little Ann with Abraham Jenkins.[xvi]

![Convict love token depicting man and ship. Reverse: JO[H]NBLOXIDGEAD. 18.15.YS 1839REMMBER MEWHEN FAR AWAY c. National Museum of Australia http://love-tokens.nma.gov.au/highlights/2008.0039.0205](https://convictionblogdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/picture11.jpg?w=640&h=639)

Convict love token depicting man and ship. Reverse side displays: JO[H]NBLOXIDGEAD. 18.15.YS 1839 REMMBER MEWHEN FAR AWAY

c. National Museum of Australia

http://love-tokens.nma.gov.au/highlights/2008.0039.0205

When asked his occupation during his interrogation on entry to the penal colony, William stated he was a seaman, like his elder brother. William’s tattoos, described by the convict clerk, reveal the future he had hoped for himself. On his right arm was a man’s head, placed optimistically next to the sun and his initial W, along with the ‘anchor and cable’ badge of seafarers and an image of a ‘boat with man’.

Prior to his final imprisonment at Yarmouth William had begun his apprenticeship at sea, serving several months aboard two ships, but then was without work for weeks. Was he looking for alternative sources of income or larking about when he was caught stealing rope from a fishing ship with another boy he knew from gaol?[xvii] When asked in Van Diemen’s Land to list his previous convictions, William described this offence, for which he served a year, as ‘letting boats adrift’. Work, play and causing mayhem shaded into each other for boys like William, roaming the streets and shore at Yarmouth without occupation, responsibility or supervision.

William had one other repeated tattoo, the initials H.L. With the exception of convicts’ own names or initials – the most common form of tattoo – initials typically referred to family members or loved ones.[xviii] H.L. may have been a sweetheart (the initials are reversed on the back of the left hand) or perhaps a Yarmouth companion or friend aboard the hulk before transportation.

There is another possibility. Henry Lavery, a forty-five-year-old gardener and groom from Worcester, was transported on the same ship as William Jenkins, leaving behind a wife and four children.[xix] The surgeon reported both convicts were well behaved aboard the Theresa. It is fanciful, perhaps, but I like to think that, separated from their families, the man and boy found comfort in each other. Having lost his own father five years earlier, did William Jenkins, in his tattoos, honour an alternative father figure as the ship transported them both to an unknown future?

William’s tattoos, listed in Marks section:

Anchor and cable mans head sun W on right arm below elbow H.L anchor and cable HL boat with man row dots and large scar & 2 small dots on left arm below the elbow LH on back of left hand 5 dots between forefinger and thumb. Ring on 2nd finger left hand, small scar on right eyebrow

[i] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, Jan 1836-Dec 1840 (Y/L2 47, Norfork PRO) and Jan 1841-Dec 1845 (Y/L2 48), 23 July 1845

[ii] For the history of amateur tattooing in Europe and America and its gradual professionalization, see Ira Dye, ‘The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818, in Proceedings of the American Philosophy Society, vol. 133, no. 4, pp. 520-554, especially pp. 528-532. Thank you to Matthew Lodder @mattlodder for pointing me to this article.

[iii] Based on analysis of Gaol Index and Receiving Book from December 25 1838 (Norfolk Record Office, Y L2/7)

[iv] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 21 August 1841

[v] Gaol Receiving Book (Norfork PRO, Y/D 41/28), 22 October 1842.

[vi] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 11 May 1844

[vii] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 28 March 1842.

[viii] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 6 March 1842.

[ix] Sarah Martin’s prisoner register, 1842, no. 120, in ‘Successive Names’ Book, Great Yarmouth Museums.

[x] Gaol Register, 24 May 1839

[xi] ‘A.J.’ in Martin’s table, ‘A Glance at Some Persons who seemed after their Imprisonment to have been Reclaimed or Improved’, 1840 [258] Inspectors of Prisons of Great Britain II, Northern and Eastern District, Fifth Report, House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online (2005), 128-29.

[xii] [Sarah Martin], ‘The Believer’s Death’, Selections from the Poetical Remains of the Late Miss Sarah Martin of Great Yarmouth (Yarmouth: James M. Denew, n.d. [1845]), pp. 60-1.

[xiii] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 14 April 1842.

[xiv] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 11 June 1844.

[xv] Gaol Index and Receiving Book, 29 April 1839; 23 January 1839.

[xvi] For William Jenkins’s conduct record and a transcription including information from various convict records on the prisoner, see http://foundersandsurvivors.org/pubsearch/convict/chain/c33a33670116. William was sentenced to transportation at the Norfolk Assizes for stealing from a dwelling house with Robert Harrod and Joshua Artis. Both these boys had been taught by Sarah Martin and supervised by her as ‘Liberated Prisoners’. For Artis and Abraham Jenkins, see Gaol Register, 24 May 1839.

[xvii] Gaol Receiving Book, 27 July 1844.

[xviii] For convict tattoos see: James Bradley and Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, ‘“Behold the Man”: Power, Observation and the Tattooed Convict’, Journal of Australian Studies, 12.1 (Summer 1997), pp. 71-97; James Bradley and Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, ‘Embodied Explorations: Investigating Convict Tattoos and the Transportation System’, in Ian Duffield and James Bradley (eds), Representing Convicts: New Perspectives on Forced Convict Labour Migration (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1997), pp. 183-203; David Kent, ‘Decorative Bodies: The Significance of Convicts’ Tattoos’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 53, (1997), pp. 78-88; Hamish Maxwell-Stewart and Ian Duffield, ‘Skin Deep Devotions: Religious Tattoos and Convict Transportation to Australia’, in Jane Caplan (ed.), Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History (Reaktion Books: London, 2000), pp. 118-35; Helen Rogers, ‘The Way to Jerusalem: Reading, Writing and Reform in an Early Victorian Gaol’, Past and Present 205 (2009), 71-104.

[xix] Henry Lavery died at the end of the year at Port Cygnet, Van Diemen’s Land, 9 December 1845.

Very interesting. I can’t say I’ve noticed details of tattoos given in Gloucester Prison’s registers, except for saying someone had a tattoo, and where it was, usually when sailors were admitted.

Thanks Jill! At Yarmouth tattoos were described in the receiving books rather than registers. not many have survived – but ones that remain contain fascinating info, sometimes on dress or on possessions prisoners had on them. I suspect tattoos were recorded more systematically later in century – to track habitual offenders etc. Would be great to see research on this and see if tattooing was concentrated in certain geographical areas and occupational sectors.

Helen

Pingback: Collectioun of Cunnynge Curioustes for November 23, 2013 | Exit, Pursued By A Bear

Lovely. Fascinating. Not strictly relevant, but I loved reading the letters of outraged South Seas missionaries about their colleagues’ children getting themselves tattooed (and circumcised). Very rebellious in its evocation of heathens, sailors and all unrespectable elements!

Pingback: Blogging Our Criminal Past, part 3: Public and Creative History | Conviction

Pingback: Tattoos are not just skin deep

Pingback: Captured Voices | the many-headed monster

Pingback: Research Blog! A closer look at Love Tokens and Convict’s tattoos. – Prison Voices: Tales from the gaol

Pingback: Anchor Me This – The Prison Twist

Pingback: Your Unfortunate Son – Prison Voices