Infanticide at the Star Inn

North Quay, Friday 16 October 1835

Sarah Bowles is up early, scouring the streets for bones and paper. She sees William Munsford driving the muck cart out of the stables at the Star Inn and follows him along the quay into Mr Powley’s yard at Laughing Image Corner.

Has he any bones for her dog? she asks the boy. There’s a piece of old meat from the privy he just emptied at the Star, William says. He found it wedged behind the privy door when he shoved it open. It’s covered in cinders but she can take it.

The woman rakes through the muck with her iron grubber. Rolling over the rotting flesh, she gasps in horror at a tiny discoloured face.

William Munsford! You have given me a child!

I didn’t know it was a child! the boy says, over and over, running for his master. I thought it was meat!

Sarah Bowles wraps the little corpse in her apron and carries it home. Gently, she washes the cold body and holds it in her arms until the man arrives to fetch it to the workhouse.[1]

Hall Quay, Great Yarmouth, showing the Star Hotel, formerly the Star Inn. Courtesy Norfolk Record Office

***

The Workhouse Infirmary, 16 October 1835

The infant male must have been between six and seven months, say the examining surgeons, when the mother gave birth about a fortnight ago. They cannot tell if it was born alive but the umbilical cord has not been tied. The right side of the head has been struck, probably when the boy shovelled it into the dirt cart.

I should think the birth was private, John Bayley tells the coroner, and without any other person assisting at the delivery.[2]

***

The Coroner’s Court, the Tolhouse, 16 October 1835

The women from the Star Inn wait to be questioned before the coroner, too anxious to speak to each other, even in hushed tones. After they heard of the baby’s discovery, there was scarce any time before the constable arrived.

Rebecca Bird is summoned first. Her husband is landlord of the Star, one of the oldest and largest taverns in town. But Mrs Bird runs the kitchen and it’s on her servants that suspicion now falls.

The privy is in the small yard at the back of the coffee room, she explains, off the long passage leading to the kitchen and stable yard. It’s a water closet for company. The servants don’t use it. They have their own convenience. The coffee room is open early for passengers waiting for the stagecoach. Perhaps the child was left in the privy by a customer? she ventures.

She has no reason to think any of her girls has been in the family way, she keeps repeating. None has been ill for the last twelve months, nor lost a day’s work.

The servants are sworn in turn, each quietly echoing her mistress’s testimony. Their room is above Mr and Mrs Bird’s: the cook and chambermaid sleeping in one bed, the laundry maid in the other, sharing with the charwoman when she stays overnight. They had not suspected a fellow servant of being with child. The boot boy backs up their statements: I have not noticed any difference in their appearance.

There’s nothing to associate the female servants with the body, concludes the coroner. They have worked at the Star several years and do not seem at all flighty. Their mistress holds them in regard. They must be respectable.

Just another sad case among the drownings and suicides that come before him, sighs George Bateman as he signs the open verdict. Firmly he addresses the court: In justice to the landlord of the Star, it ought to be mentioned that nothing has transpired calculated in the slightest degree to connect any one of the inmates with this strange affair.

But the coroner orders a handbill be circulated, asking for information that might lead to the mother.[3]

Coroner’s Inquest Indent, 16 October 1835, Norfolk Record Office, Y/S 3/146

***

24 October 1835

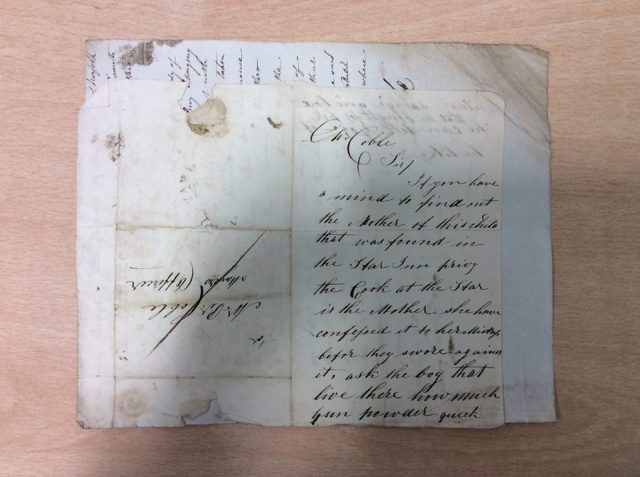

Peter Coble, Sergeant at Mace opens the anonymous letter, scrawled by an unpracticed hand and pushed under his door.

Sir

If you have a mind to find out the Mother of this child that was found in the Star Inn privy the Cook at the Star is the Mother she has confessed it to her Mistress before they swore against it, ask the boy that live there how much Gun powder quick silver savige and box that he bought for her he can tell you if he like

The cook at the Star is remanded on suspicion of concealing the birth of her child and a new witness comes forward.[4]

Anonymous letter sent to Peter Coble, Constable. Examination Papers, 26 October 1835, Norfolk Record Office Y/S 3/146

***

The Magistrate’s Court, the Tolhouse, 26 October 1834

She was preparing Sunday dinner, about a month ago, Mary Chase tells the Mayor, when the young woman called. She said she was Ann Westgate and was asking for George Myhill. What’s my nephew done now? thought Mrs Chase. Only yesterday he’d left a good place as waiter at the Star Inn.

The stranger looked uncomfortable and began to cry. She was cook at the Star and on leave for the day, but she had nowhere to go. Since the miserable girl would not eat any dinner, Mary led her upstairs to rest.

Fighting back tears, Ann Westgate told how George had put her in the family way. Now she was five months gone. She grabbed Mary’s hand and pressed it against her belly then squeezed a few drops of milk from her breast to prove her predicament.

George had behaved very roguishly and refused to marry, she sobbed. What was she to do? She had sent the errand boy out for forcing medicine a great many times. The chemist did not know till yesterday she was with child. He said he very sorry to have given the medicine, for now the baby was low. She must be strong in constitution, he said, for she had taken enough medicine to kill ten children.

She might stay the night, Mary told the distraught visitor, but by morning the girl had gone.

Last Thursday, says Mrs Chase, finishing her evidence, a little boy came to my husband’s house and said the cook wanted to see me. She had some good news to tell me. I did not go and afterwards heard of a child being found in the privy of the Star Tavern.[5]

***

The Magistrate’s Court, the Tolhouse

As she is ushered into the court for re-examination, Mrs Bird glances at her cook, standing forlornly and twisting her hands in the folds of her skirt.

Prior to Michaelmas, the landlady says in answer to their questions, Cook was ill but not ill enough to keep to her bed. One morning she said she had been very unwell during the night and I went to look at the bed.

Rebecca Bird lowers her eyes. How can she speak of such things to the gentlemen?

It was not worse than it might be with other females on an ordinary occurrence, she says in a small voice. I said to Mrs Roberts, the charwoman, to go and wash the things out of the way and I observed to Mrs Roberts that the bed was spotted.

They press her about Ann Westgate.

I have accused Cook since the child was found of having a miscarriage, she tells them. She said she never had a child or anything like a child.

The mistress catches the terror in her servant’s eyes. Anybody says about the town—“It is the Cook’s”—I cannot tell, she adds quickly.

The charwoman speaks more frankly than her mistress when answering the probing questions. She comes in from Hopton when the Star gets busy, Sarah Roberts explains, to help with the laundry and cleaning. She was not there when the baby was found but three weeks ago, late in the morning, Cook was taken with a violent stomach pain. You must have some gin, she told Cook, and fetched her half a pint, which she drank with some water. Cook lay down for an hour before coming back to work but she was the first to bed that evening.

When the charwoman rose next morning at five o’clock, Cook said she was a great deal better, whispering so as not to disturb their sleeping companions. Please would Mrs Roberts be so kind as to air her petticoat and shift? She had spotted them in the night. The following morning, Cook asked her to clean the bedding. Do not mention it to the others, she pleaded, or let them see the sheets. She could not help it. She had been very poorly.

Oh dear me, Mrs Roberts, the Mistress said later that morning, what a state the Cook’s bed is in! Do you go and do what you can with it. I cannot think what has happened to Cook!

But the charwoman had her doubts. There was something more than common–she tells the Mayor–the bed spotted with blood to a large round. From the appearance I suspected Cook had miscarried.

Sarah Roberts bristles as they bombard her with questions. I never went for any medicine for Cook or was ever sent for any. Never saw her take any medicine. No, indeed, I never put anything into the privy at the request of Cook. I had never heard that Cook was in the family way.

Mrs Roberts will not have her reputation smeared. Last Monday, she tells the Mayor, I came to the Star Tavern and said to Mrs Bird, “Oh dear me, is this true about Cook and a child being found? What a piece of work this makes.”

I know nothing more, the charwoman says emphatically.

The chambermaid sleeps with Ann Westgate. Will they think she knows more than she can say, Elizabeth Parker wonders?

She went to bed three hours after Cook, she tells them. They had no conversation and not once did Cook disturb her. In the morning, she whispered with the charwoman and laundry maid about the bedding.

It was talked of that Cook was with child. I did not believe it, Elizabeth says vehemently. I mentioned to Mrs Bird the state of the bed. She said it was no more than she had seen of another woman. Won’t they see she is just the chambermaid? Why should she question her mistress?

Still she cannot condemn Ann Westgate. It has been suspected from Cook being ill, and the child being found, and the state of the bed, that Cook was the mother of a child, the chambermaid says, noncommittedly. It is not until she leaves the stand that Ellen dare look at her friend.

The youngest servant, the laundry maid Mary Ann Wright, is less circumspect.

Cook was not very well. She did not get her dinner with us. I cannot say whose child it was that was found. Everyone in the house say they know nothing about it. I have heard it talked of about the child being found, and I have been asked whether it was Cook’s. I have said, if it was Cook’s, it was a shocking thing. I suspect it was Cook’s child.

The magistrates confer over the statements. Could the cook have carried the child and gone into labour without anyone noticing at the Star? There is no proof she had assistance but, with Mary Chase’s account of the visit from the pregnant woman, there’s enough to charge Ann Westgate with concealing the body of her newborn child.

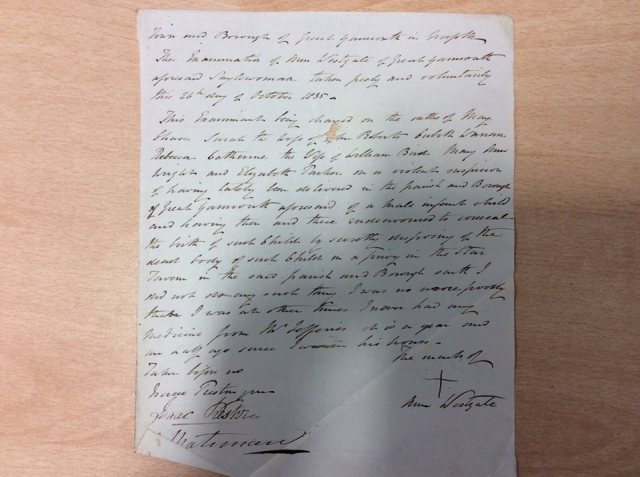

I did not do any such thing! is all Ann Westgate can say when she is indicted on the sworn testimony of her friends. I was no more poorly than I was at other times. I never had any medicine from Mr Jeffrey. It is a year and a half ago since I went to his house.[6]

Ann Westgate’s Indictment and Examination Statement, 26 October 1835, Norfolk Record Office Y/S 3/146

***

Almost certainly Ann Westgate was the mother of the child yet she was found not guilty of concealing its birth.[7] There are no records of the five months she spent in prison awaiting trial and no newspaper reports to indicate why she was acquitted, despite the press interest when the body was found. But the examination statements taken before she was charged—and their inconsistencies—tell us much about responses to pre-marital sex and its consequences, whose burdens fell mostly on women.

Except for the muck boy who found the body and the boot boy who polished the shoes in the passageway leading to the privy, the witnesses were all women. No one expected the landlord to know of his female servants’ affairs, though it was Mr Bird the coroner mentioned when absolving his staff of involvement in the suspicious death. While the landlady was interrogated about what she knew of her servants, no suspicion fell on her although, aged about forty, Rebecca Bird was within childbearing years. It was unthinkable that a respectable married woman might conceal her pregnancy.

Neither was George Myhill—the child’s father according to his aunt—called for questioning. Unless putative fathers were named as perpetrator or accessory in cases of infanticide and concealment, legally their testimony was deemed irrelevant, even though desertion was recognized as one of the main factors driving unmarried mothers to terminate their pregnancy or kill a newborn.[8]

Could George have sent the incriminating letter? The handwriting does not match the signatures of the witnesses who were examined. But its sender must have been close to Mary Chase to believe Ann Westgate had taken forcing medicine. And the writer seemed acquainted with goings-on at the Star, accusing the landlady of knowing about the unwanted pregnancy. George Myhill may have born a grudge. Had he walked away from his post at the tavern after Ann threatened to reveal his perfidy, or had Mrs Bird sacked the waiter for failing to stand by her cook?

Neither was John Jeffrey called for examination, the surgeon and chemist on Church Plain who unwittingly prescribed medicine to the pregnant woman, according to Mary Chase.[9] Prosecutions for administering abortions or supplying abortificants were unusual in the nineteenth century, largely because of the difficulty of securing evidence.[10] Surely Jeffrey, like doctors named in similar cases, would have denied giving Ann Westgate medicine or knowing she was pregnant? But the authorities may also have been reluctant to put a respectable doctor on the stand and implicate him in child murder.

Investigating Ann Westgate’s alleged use of forcing medicine would have meant pursuing a charge of wilful killing that would be difficult to prove, especially since there was no eyewitness to confirm the child was born alive. Aborting a pregnancy before quickening (around four to five months) could be punished by a fine, imprisonment, or transportation up to fourteen years. If it was judged that quickening had taken place, Ann Westgate could have been sentenced to execution.[11]

But juries were notoriously reluctant to convict women of intentional killing, especially when they had been deserted—like Ann Westgate—as were the majority of women brought to trial. In the ten cases of infanticide tried at the Central Criminal Court in London in the 1830s, for example, five women were acquitted. The other five defendants were exonerated of murder but found guilty of the lesser crime of concealing a birth, introduced in 1803 precisely to facilitate convictions. All five women were sentenced to two years imprisonment.[12] No wonder the Yarmouth magistrates opted to charge Ann Westgate with concealment.

Surely the cook delivered her baby alone, since the umbilical cord was not tied. Most likely she gave birth in the privy—the only room on the busy premises where she could hope for privacy—or in the servants’ bedroom after retiring early with stomach cramps, then hiding the little corpse until the water closet was due to be emptied. Privies—spaces that were both public and private—were among the most common places to conceal a birth, where at least four of the ten women tried at the Old Bailey in the 1830s hid their babies.[13] Domestic service was by far the largest occupation of women prosecuted for infant deaths.[14] Concealing and disposing of a pregnancy was particularly challenging for servants, since their physical changes and movements were liable to be noticed by inquisitive employers and fellow workers.

John Constable, Yarmouth Pier (1822), courtesy Denver Art Museum

But perhaps the most striking feature of Ann Westgate’s case, that makes it touching as well as tragic, was the efforts of her friends to protect her from detection and then conviction. The landlady and chambermaid avoided incriminating Ann Westgate, even though they risked perjury or being fingered as an accomplice. Did Rebecca Cook lean on the charwoman and laundry maid to qualify their testimony when they took the stand at the trial? Did someone ask Mary Chase to change her earlier account of the visit from the cook?

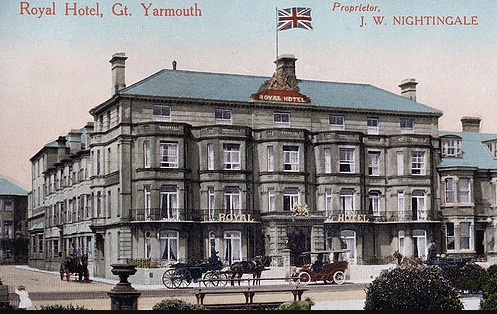

Rebecca Bird continued to show solidarity with Ann Westgate, welcoming her back as cook at the Star Inn after her acquittal at the Quarter Sessions on 4 April 1836. Three years later Ann moved with the landlord and landlady when they opened their grand new establishment, the first on the seafront. Gentlemen seated in the Hotel, boasted the Birds, would enjoy a Panoramic view of the Sea, with its undulating bosom studded by hundreds of vessels coasting within 300 or 400 yards of the house. There, Ann Westgate delighted diners with excellent viands and seasonal delicacies, including meetings of the most influential gentleman and merchants of the town, hosted by the Mayor. She would remain with the Birds till her death in 1852.[15]

Formerly Birds’ Royal Hotel. Courtesy of Great Yarmouth Local History and Archaeology Society

***

Birds’ Royal Hotel, 13 January 1849

Charles Dickens opens his eyes and throws back the sheets. He’s hungry already, in spite of dining late with John Leech and Mark Lemon, after their long windswept walk to Lowestoft and back. The shivering adventurers were grateful for their hearty supper. Mrs Bird, he insisted, must bring Cook to the table so they could toast her good health over brandy and cigars. Beaming with pride, the cook’s rosy cheeks flushed even redder as the Inimitable Boz signed the menu with a flourish. For breakfast, she has promised to serve him a Yarmouth Bloater—the finest herring in the world, she says.

He opens the curtains and looks out onto the shore, bathed in the winter pale of early morning light. He scans the wide yellow sands for the overturned boat, home to the jovial beachman they met yesterday. It is the strangest place in the wide world, he thinks of Yarmouth, and yet there’s something about this flat landscape and its weather-beaten people that commands his attention. He can feel the beginnings of a story taking shape.

Buffeted by the wind, two children are fighting their way up the beach, the boy holding onto his cap, the little girl’s curls streaming behind her. He would have loved it here as a child, stooping to pick up shells and prodding the jellyfish, chasing the seagulls and scouring the horizon for tall ships. His eyes are pulled towards the tideline.

And then he sees her—a solitary figure, hugging her shawl and gazing out to sea as the waves break at her feet. There’s always a girl with a sad tale. Who will cause her sorrow and who will save her?[16]

Little Emily, By Phiz (Halbot Browne). From David Copperfield, serialized May 1849 – November 1850. Courtesy David Perdue, Charles Dickens Page.

Many thanks to Daniel Grey @djrgrey for sharing his research on infanticide with me.

[1] Examination statements taken 16 October 1835, Quarter Sessions Papers, 4 April 1836, Norfolk Record Office, Y/S 3/146.

[2] Information of Harry Worship and John Bayley, surgeons, before the Coroner, George Bateman, 16 October 1835, Y/S 3/146.

[3] Examination statements and Inquest Indent, 16 October 1835, Y/S 3/146; Ipswich Journal, 24 October 1835, p. 3.

[4] Examination Statement, 26 October 1835, Y/S 3/146; Gaol Register, 24 October 1835; Bury and Norwich Post, 28 October 1835 p. 3; Norwich Mercury, 31 October 1835, p. 3

[5] Mary Chase lived in Row 80. Examination Statement, 26 October 1835, Y/S 3/146,

[6] Examination statements, 26 October 1835, Y/S 3/146.

[7] Norfolk Chronicle, 9 April 1836, p. 2; England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009.

[8] In her study of infanticide in Ireland, Elaine Farrell found that putative fathers were named in only 6% of the cases she examined; 84% of the babies in her cases were illegitimate. See ‘A Most Diabolical Deed’: Infanticide and Irish Society, 1850–1900 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013) pp. 29 and 26.

[9] John Gifford Jeffrey, surgeon, 1839 Pigot’s Directory.

[10] R. Sauer, ‘Infanticide and Abortion in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, Population Studies, 32.1 (1978): 81-93; Angus McClaren, ‘Abortion in England, 1890-1914’, Victorian Studies, 20.4 (1977): 379-400.

[11] Sauer, ‘Infanticide and Abortion’, pp. 83-4

[12] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2 March 2015). Search for all offences where offence category is infanticide, between January 1830 and December 1839. https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_offences_offenceCategory_offenceSubcategory=kill_infanticide&fromYear=1830&fromMonth=01&toYear=1839&toMonth=12&start=0 accessed 12 April 2017. The earliest official statistics on infanticide record the deaths of 76 children under the age of one in England and Wales between 1838 and 1840—amounting to one third of murders in that period; cited by Sauer, ‘Infanticide and Abortion’, p. 81. See Sauer, p. 83 for the 1803 Act. By the end of the century, estimates Daniel Grey, only a third of cases involving the killing or neglect of a newborn resulted in a murder charge. In over forty percent of these cases, the defendant was charged with concealment instead, most of who received a fine or less than a month’s imprisonment. See Daniel J.R. Grey, ‘Discourses of Infanticide in England, 1880-1922’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, Roehampton University, 2008), pp. 151, 176-8, 183.

[13] See also Farrell, ‘A most diabolical deed’, p. 25.

[14] In Farrell’s sample, seventy percent of women charged with infanticide or concealment were described as domestic servants. See ‘A Most Diabolical Deed’, p. 31.

[15] 1841 Census, Class: HO107; Piece: 794; Book: 1; Civil Parish: Great Yarmouth; County: Norfolk; Enumeration District: 2; Folio: 34; Page: 12; Line: 5; GSU roll: 438872; 1851 Census, Class: HO107; Piece: 1806; Folio: 143; Page: 11; GSU roll: 207457-207458, Ancestry.com. I think she was born 25 March 1810, baptized the following day as Mary Ann Lydia Westgate, and buried 15 June 1852, aged 42; see Ancestry.com. Norfolk, England, Bishop’s Transcripts, 1685-1941 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. For Birds’ Royal Hotel, see Norfolk Public Houses, http://www.norfolkpubs.co.uk/gtyarmouth/gyr/gyroh.htm; Norwich Mercury, 27 July 1839, p. 2; Norfolk Chronicle, 25 January 1840, p. 3; Norwich Mercury, 25 January, p. 3. 1841 Census.

[16] Charles Dickens began work on the novel that would become David Copperfield after staying at the Royal Hotel in Yarmouth, 12 January 1849. On the walk that day from Yarmouth to Lowestoft, Dickens noticed the sign to Blunderston in Suffolk that he changed to Blunderstone Sands for David Copperfield’s birthplace. See letter to Mrs Watson, 27 August 1853, The Nonsuch Dickens: The Letters of Charles Dickens, edited by Walter Dexter (1938) Vol. II, p. 484. I shall certainly try my hand at it, Dickens wrote of Yarmouth to his friend John Forster, and his mind, he said, was fixed on names like running on a high sea; see John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens, (London: Chapman Hall), Vol. 2, pp. 55-8. The menu signed by Dickens is still displayed at the Royal Hotel in Yarmouth.

A fascinating and in many ways a heart-warming story, given the tragic circumstances. History come to life.

Thank you John! Another very moving case to work on.