What has that old villain been doing to you?

The following story is based on documentation of a historical case of child sexual abuse, including the victim’s testimony.

The Conge Row, Great Yarmouth, 16 May 1842

Wending her way home from market with her morning shopping, Ruth Hastings spots a boy staggering out of the house belonging to John Gray Hudson. The widow is alarmed, having five children of her own. She pauses and looks carefully. The boy seems to be limping painfully, with one hand in the flap of his trousers. There’s sand on the back of his jacket, the dressmaker notices.

‘What has that old villain been doing to you?’ she calls out to the child.

The boy looks at the lady, trembling, but does not speak.

Gently, Ruth Hastings asks his name and where his mother lives. Then, taking John Scales by the hand, she leads him slowly round the corner home.[1]

Congo Row, Great Yarmouth, c. 1860s? Courtesy Norfolk City Council

***

Mary Ann Scales and her husband Hugh, a fisherman, were in their cottage on Row 29 when Mrs Hastings brought back their thirteen-year-old son.[2] Someone must have alerted the constable directly for John Gray Hudson, aged 51, was committed immediately to the gaol. At the magistrate’s court, the following day, he was questioned before the Mayor and indicted to stand trial at the next Quarter Sessions.[3]

John Scales was also examined in the presence of his assailant. Informants’ testimony at the magistrate’s court was not transcribed verbatim and we have to surmise the questions that they were asked. Still, the boy’s account, taken by the clerk, will have been close to the record. It is worth reproducing in full, for testimony by victims of sexual abuse has rarely survived, especially related so soon after the incident.[4] John’s short answers reveal much about relationships between children and adults among the working community who resided in the narrow lanes that criss-crossed the port town. They indicate, too, the expectations of children’s behaviour that could make them vulnerable to sexual predators.

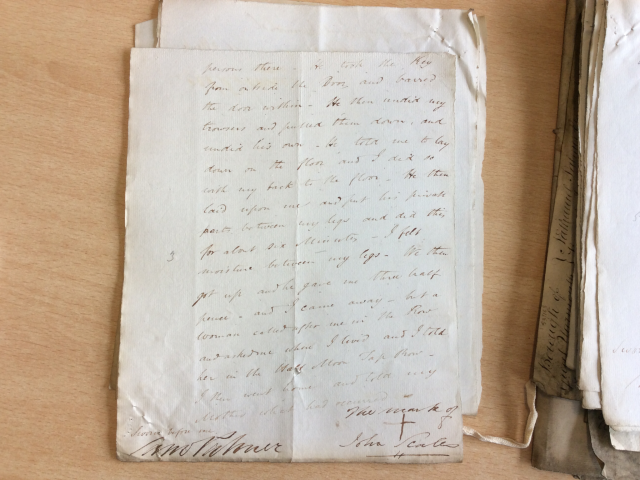

I live at home with my father and mother in the Half Moon Tap Row in Great Yarmouth. I know the person now present John Gray Hudson who used to sell Shrimps for my Mother. I saw him yesterday morning about 9 o’clock in the Market Place. He said to me ‘You must come down to my House a little after 10’. And about 10 same fornoon he came to my House. I was braiding Shrimp Nets in the big low room. My father and mother were in the small room—the Kitchen. Hudson went out and I followed him to his House in the Conge Row. We both went in. There were no other persons there. He took the Key from outside the Door and barred the door within. He then undid my trowsers and pulled them down, and undid his own. He told me to lay down on the floor and I did so with my back to the floor. He then laid upon me and put his private parts between my legs and did this for about six Minutes. I felt moisture between my legs. We then got up and he gave me three half pence—and I came away. But a Woman called after me in the Row and asked me where I lived and I told her in the Half Moon Tap Row. I then went home and told my Mother what had occurred.

Information or Examination of John Scales, 17 May 1842. Courtesy Norfolk Record Office. Probably John could neither read nor write for he signed his name with his mark.

The record of the boy’s testimony does not indicate how John Scales felt when he was assaulted, nor when he gave evidence. Did he stutter in a small voice, in trepidation at speaking on oath before the formidable person of the Mayor and the scowling man he accused? Or did he speak out angrily and defiantly? Yet somehow his simple, matter-of-fact statement speaks volumes about the shock felt by the child when his trust was abused.

The labourer, John Hudson, was a familiar visitor at the fisherman’s house that was always crowded and busy, with the nine children belonging to the Scales scuttling in play or labouring over their chores. Selling shrimps for Mrs Scales was one of the many casual jobs by which Hudson made his living. That morning, when he called, perhaps Mary Ann was shelling shrimps, freshly caught by her husband. Did he greet the fisherman and his wife in their kitchen or sneak, unobserved, into the front room after seeing the boy in the window, mending his nets? Whether the child had forgotten Hudson’s invitation or chosen not to pay him a visit, he obediently put down his work and followed the man. Children were expected to do as adults bid them.

Hudson, it appears, had planned the attack, knowing that at ten o’clock his elderly mother would be picking her way slowly around the market. Did John become alarmed when Hudson drew the bolt, for doors were rarely locked in daytime? In a daze, it seems, the boy did as he was instructed, his awareness of time—six minutes—the only hint of how he registered the inexplicable molestation. He took the halfpennies, meant to buy his silence. Would he have said anything to his mother had not Ruth Hastings stopped him in the street?

Boy with basket and shrimping net by John Sell Cotman (1782-1842) Pencil on paper, 1836. Courtesy Norfolk Museums

***

Cases concerning the sexual abuse of children seldom came to trial in the nineteenth century. Unless an independent witness could testify to the offence or there was clear physical evidence of sexual assault, charges were difficult to prove.[5] It is no surprise that when the constable apprehended Hudson ‘for his bad conduct to a boy’, the accused retorted ‘that was to be proven’ and refused to say more. When indicted for ‘unlawfully and indecently assaulting’ the boy, aged between twelve and thirteen years, Hudson maintained his silence: ‘I decline to say any thing at present’.[6]

Fortunately for the prosecution, another neighbour was able to corroborate the timing and sequence of the events described by John Scales and Ruth Hastings. The mariner’s wife, Mary Ann Sheppardson, lived on the Conge Row opposite Hudson and said she saw the ‘little boy’ enter his house and come out twenty minutes later. She watched the boy ‘walking in a very curious posture, with one hand on his back and appearing to be scarcely able to walk’.[7]

In this case, unusually, there was physical evidence that supported the boy’s statement. It is unlikely that penetration had taken place, though this was not categorically stated in the information documents. The surgeon who examined John Scales found no injury to his person but discovered on the boy’s shirt ‘at the lower part of the hind flap a stain which I verily believe to have been caused by a seminal emission’. In the record of the surgeon’s examination, the word ‘virile’ is crossed out and the word ‘seminal’ inserted instead.[8] The correction strongly suggests the surgeon’s hesitancy in describing the semen, as if searching for the right word. His hesitancy also reflects the euphemistic language surrounding both sexual acts and sexual violence at this time, which could make even a medical man stumble over his words.

In the rare event of child sexual abuse cases coming before the courts, they tended to receive little press coverage unless the offence involved extreme violence or fatality. Newspapers used a variety of stock phrases to characterise these crimes, such as ‘indecent’, ‘abominable’ or, most commonly ‘unnatural’, often observing that ‘the evidence is not such as we can lay before our readers’.[9] When Hudson was found guilty, his conviction was noted only briefly in a local newspaper as ‘assaulting and attempting to commit an unnatural crime against John Scales, a boy between 12 and 13 years of age’. No further details of the incident were supplied.[10] Hudson’s offence was entered in the Criminal Register with the similarly euphemistic term ‘unnatural misdemeanour’.[11]

A new statute in 1828 consolidated and amended existing laws in England relating to offences against the person. It was designed, in part, to improve conviction rates for interpersonal violence, since juries often proved reluctant to find the accused guilty for all but the most heinous of crimes.[12] Cases of murder, manslaughter, rape, sodomy and bestiality continued to be defined as felonies that had to be tried by jury, as well as those involving ‘the carnal knowledge’ of a girl or the sodomizing of a boy under the age of ten years. Evidence of penetration alone, rather than emission as hitherto, was to be admissible as proof of rape and sodomy. Though subject to the death sentence, as before, judges now had the discretion in such cases to replace a capital sentence with transportation, as ‘death recorded’. By contrast, sexual assaults on children of both sexes aged between ten and twelve years old were reclassified as misdemeanours, as indeed were most forms of assault. Such misdemeanours could be tried summarily by two magistrates and punished, in the first instance, by a fine of £5 plus costs or, in default of payment, by imprisonment of up to two months. At Yarmouth, significantly, the magistrates interpreted the upper age limit for child victims as ‘between eleven and thirteen years’. Consequently, in three of the five cases that came before them in the years 1839-43, three of the children were aged thirteen years old, including John Scales.

It is difficult to establish why some sexual misdemeanours were dealt with summarily and others referred to the criminal courts since decisions made by the sitting magistrates were rarely recorded in any detail. Of the five men at Yarmouth charged with molesting a child, John Hudson was one of only two suspects sent for trial by jury. Two men were found guilty by the sitting magistrates of each taking ‘indecent liberties’ with a girl and served sentences of two months in default of the £5 fine. Both were itinerant musicians who will have made much of their income playing in the taverns, where Jean Baptiste Pattisor may well have gained access to ten-years old Sarah Grimble, whose mother ran the Beehive which the Gaoler considered a ‘house of ill fame’.[13] It is possible that Mrs Grimble preferred the magistrates to try the case rather than risk drawing further attention to her house and business in open court. Prosecutors may also have chosen to save their child from giving evidence at the Quarter Sessions or simply not have had the funds to lay down the £20 recognizance pledging to appear in court.

When a pauper inmate was accused in February 1839 with assaulting a young girl in the workhouse, however, the magistrates themselves may have had good reason to keep the incident out of open court, for it was claimed that George Boulton had previously molested several children between the ages of eleven and thirteen in the three years he had been resident within its walls. As justices of the peace, the magistrates had overall responsibility for administering the widely hated New Poor Law. Antipathy towards the pauper ‘Bastilles’ was a major cause of agitation for the Charter and popular condemnation was often accompanied by allegations against workhouse officials for cruelty towards inmates, including sexual exploitation. Quite possibly the Yarmouth workhouse master or the Board of Guardians had sought to keep the earlier allegations ‘in house’. Did the charge against Boulton threaten to expose them for turning a blind eye to an old pauper interfering with children in their care? While there is no record of the sitting magistrates criticising the workhouse officials, they expressed frustration in not being able to impose a harsher punishment on Boulton. Sentencing him to the fine or two months imprisonment, the Mayor pronounced ‘that his conduct to the children was most infamous, and that he regretted he had not the power to commit him for six months, and have him flogged around town.’[14]

Cases referred to the assize courts may have been those deemed most serious and with strong supporting evidence. In the five years 1839-43, five men were prosecuted at the Central Criminal Court in London for ‘assault with intent’, the only category of sexual offences which included assaults on minors. Their victims were all girls, four under ten and one eleven years old. All five men men were convicted, though evidence of assault on a girl under ten years was not brought before the court when the accused pleaded guilty to common assault. Each man served a prison sentence ranging between three to eighteen months.[15] At the Yarmouth Sessions, by comparison, Benjamin Warren received a much lighter session when convicted of ‘a violent assault, with intent to commit rape’ on a little girl of ten ‘under the most revolting circumstances’. Described by one newspaper as ‘a respectable looking man’, Warren’s social status seems to have been taken into account, however, when bail was set at an unusually high rate, —£100 himself and two sureties of £50 each, stood by his brother and ‘a gentleman’. He was sentenced to a mere fourteen days imprisonment though with a £50 fine—considerably steeper than those usually set by the court—and, if he did not pay, extension of imprisonment up to a year. Able to pay off the fine immediately, Benjamin Warren was saved the ignominy of imprisonment after a fortnight inside.[16]

Statements made at a later trial in 1845 suggest that damage to reputation was considered by the court to be as much a punishment as imprisonment for ‘respectable’ men, like the sea captain. On this occasion, a hairdresser was found guilty on the word of a girl ‘between the tender age of eleven and twelve’, of forcing her ‘to hold his member’ while curling her hair, as also witnessed by his assistant. In pronouncing sentence, the Recorder condemned George Walton ‘of an offence hardly to be named… which tends more than any to the demoralization of society’ in which he had sought ‘to debase the child of a poor man’. As a ‘respectable tradesman’ and family man, the Recorder’s admonishment continued, ‘you will be an outcast from society’ and lose ‘caste… your position, character, and business’. The shame he had brought upon himself might be sufficient punishment, warranted the Recorder, did he not think Walton would benefit from a term of imprisonment to reflect on how ‘to lead a better life in future’. The sentence of one month in prison with a fine of £50 was met with a ‘burst of applause’ around the court that ‘could be suppressed only with difficulty’.[17]

John Hudson’s sentence of eighteen months imprisonment with hard labour was, therefore, comparatively lengthy by the standards of the Yarmouth Quarter Sessions. Almost certainly, the severity of the sentence was a consequence of reference at the trial to a former charge brought against Hudson in 1812, aged twenty-three, of a carnal assault on a girl of ‘tender age’.[18] The case was brought by a cabinetmaker’s wife on behalf of her ten years-old daughter. She had left her child in the care of Hudson while she worked upstairs at home. On hearing her daughter call out, she had come down to find Hudson with his breeches round his ankles having attempted to rape the girl. At his trial, nine months later Hudson was acquitted. Had he been found guilty, he may have been sentenced to death, as was John Hannah, convicted at the same Sessions, of murdering his wife and the last man to be hanged in Great Yarmouth.[19]

‘What has that Old Villain been doing to you?’ Ruth Hasting’s question to the distressed little boy suggests she had long harboured concerns about John Hudson, the single man who lived alone with his mother, now in her eighties.[20] Did his neighbours remember the old case and gossip about his ‘unnatural’ habits, while keeping their children from him? ‘I suspected something wrong of Hudson’, Mary Ann Sheppardson told the Mayor, ‘and communicated my suspicions to Mrs Hastings, a Neighbour’. Had Mary Ann actually noticed the boy enter and leave her neighbour’s house? Or did she concoct her witness statement with her friend Mrs Hastings in order to make sure that, this time, the notorious abuser would not escape justice?

***

When admitting Hudson to gaol prior to his trial, the governor took care to note the prisoner’s acquittal in 1813 for assaulting an infant girl. This suggests the gravity with which the authorities viewed the current charge. Someone must have been tasked with looking through thirty years of records in search of the man’s former committal. The gaoler also recorded the precautions he had taken in confining Hudson:

Committed for trial charged with an indecent Assault upon a little boy. I have placed him in the first ward, as at this time there are no boys therein and it also being subject to immediate inspection.[21]

Joshua Artis, one of the ‘men’ in the gaol room with Hudson, was only sixteen years old but no longer a juvenile in the eyes of the gaoler, and therefore not at risk.

If Hudson’s cellmates knew of his crime it does not appear to have affected their friendship. Soon all would be sent to their cells for ‘laughing and making noise’. Hudson’s inclusion in the inmate camaraderie may have been helped by favours from outside. The elderly Mrs Hudson was twice reproved for smuggling tobacco into the gaol in a handkerchief for her son. She would not—or could not—acknowledge the guilt of the son who kept a roof over her head.[22]

John Gray Hudson would not be convicted again and died in 1849.[23] The year before, aged nineteen, John Scales married Susannah Sutton. Like his father, John worked as a fisherman and dealer. By 1861, he and Susannah had five children. He died in 1868, at thirty-nine-years-old.[24]

Shrimpers on the Bure by Arthur Verey (1840-1915). Courtesy Great Yarmouth Museums. Pictured from the north side of Yarmouth, where John Scales lived all his life.

[1] Examination of Ruth Hastings, 17 May 1842. The examinations in this case are from Rex v Hudson, Great Yarmouth Borough Sessions, 21 June 1842, (Norfolk Record Office, Y/S 3/163/7). For Ruth Hastings, living on Conge Row (Row 28), see 1841 Census, Class: HO107; Piece: 793; Book: 6; Civil Parish: Great Yarmouth; County: Norfolk; Enumeration District: 11; Folio: 13; Page: 18; Line: 3; GSU roll: 438872; 1851 Census, Class: HO107; Piece: 1806; Folio: 132; Page: 37; GSU roll: 207457-207458.

[2] 1841 Census, Class: HO107; Piece: 793; Book: 6; Civil Parish: Great Yarmouth; County: Norfolk; Enumeration District: 11; Folio: 10; Page: 13; Line: 4; GSU roll: 438872. John Church Scales was baptised 14 January 1829: see Norfolk Record Office, Norfolk Church of England Registers, Y/WE 1-67; (Ancestry.com).

[3] 16 May 1842, Great Yarmouth Borough Gaol Register, Norfolk Record Office, Y/L2 9.

[4] Examination of John Scales, Rex v Hudson, Y/S 3/163/7.

[5] Trials involving the sexual abuse of children rose from the 1830s but resulted in convictions in probably less than a third of reported cases finds Louise Jackson. See her Child Sexual Abuse in Victorian England (London: Routledge, 2000), p. 3. Cases involving the abuse of girls were far more common than boys, since only female innocence was presumed compromised by carnal knowledge. Victoria Bates traces the developing role of forensic science in such cases; see Sexual Forensics in Victorian and Edwardian England: Age, Crime and Consent in the Courts (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). One place where the sexual abuse of boys did often come to light, however, was in the navy. See B. R. Burg, Boys at Sea: Sodomy, Indecency and Prosecution in Nelson’s Navy (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007).

[6] Examination of John Gray Hudson, Rex v Hudson, Y/S 3/163/7.

[7] Examination of Mary Ann Shepardson, Rex v Hudson, Y/S 3/163/7.

[8] Examination of Henry Worship, surgeon, Rex v Hudson, Y/S 3/163/7.

[9] See for example the ‘assault on Mary Ann Banks’, discussed below, as reported by the Norfolk News, 18 October 1845, p. 3.

[10] Suffolk Chronicle; or Weekly General Advertiser & County Express, 25 June 1842, p. 3. Baptized 14 January 1829, John Scales was aged thirteen when he was assaulted; Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Christening Index, 1530-1980 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2008.

[11] Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 [database on-line] Class: HO 27; Piece: 67; Page: 389.

[12] 9 Geo. IV. c. 31, An Act for consolidating and amending the Statutes in England relative to Offences against the Person, 27 June 1828, cited in John Frederick Archbold, The Law Relative to Commitments & Convictions by the Justices of the Peace (London: W. Benning, 1828) pp. 361-378. For an invaluable discussion of the 1828 statute and its implications for the regulation of sexual offences in the early and mid Victorian period, see Charles Upchurch, Before Wilde: Sex Between Men in Britain’s Age of Reform (University of California Press, 2013), pp. 91-104.

[13] Gaol Register, (James Durrant) 12 August 1840 and (Jean Baptiste Pattisor) 13 December 1841. Mrs Sarah Grimble was remanded for two days on suspicion of receiving stolen goods; see Gaol Register, 18 February 1839.

[14] Gaol Register, 19 February 1839; Bury and Norwich Post, 27 February 1839, p. 3.

[15] Tim Hitchcock, Robert Shoemaker, Clive Emsley, Sharon Howard and Jamie McLaughlin, et al., The Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 1674-1913 (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, March 2018). Accessed 7 October 2019. Searched for all offences where offence category is assault with intent, between 1839 and 1843. 42 cases in total, though one result is repeated so assaults on minors represent 13% of this category. See https://bit.ly/2MlmvxG for results. Other relevant categories (rape, indecent assault, sodomy, and sodomitcal intent, and ‘other’) do not contain entries specifying the victim was a minor.

[16] Gaol Register, 20 June 1843; Norfolk Chronicle, 13 May 1843, p. 3; Norfolk Mercury, 13 May 1843, p. 3; and Norfolk Chronicle, 20 May 1843, p. 3.

[17] Rex v Walton, Yarmouth Quarter Sessions, 10 October 1845, Y/S 3/174; Suffolk Chronicle, 18 October 1845, p. 2.

[18] John Hudson, carnal assault on an infant female, Yarmouth Quarter Sessions, 1 September 1813. Acquitted. Class: HO 27; Piece: 9; Page: 222, Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 [database on-line]

[19] Information of Mary Ann Custance, 16 December 1812, Quarter Sessions, 1 September 1813, Y/S 3/109; England and Wales Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009 (HO 27; Piece: 9; Page: 222).

[20] John and Mary Hudson, Row 28, 1841 Census, HO107; Piece: 793; Book: 6; Civil Parish: Great Yarmouth; County: Norfolk; Enumeration District: 11; Folio: 16; Page: 25; Line: 5; GSU roll: 438872.

[21] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 17 May 1842, Jan 1841-Dec 1845, Norfolk RO, Y/L2 48.

[22] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 11 October 1842 and 19 July 1842.

[23] John Scales, Burial 12 September 1849, Ancestry.com. Norfolk, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1990 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016.

[24] John Scales and Susannah Sutton, Marriage, 7 November 1848, Ancestry.com. Norfolk, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1940 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016. John Scales, Row 30, 1861 Census, Class: RG 9; Piece: 1192; Folio: 163; Page: 29; GSU roll: 542772. Death Jan-March 1868, FreeBMD. England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006.

Pingback: Crime links for October 2019 – Nell Darby

What a fantastic blog and I love the referencing!

Would you be interested in researching together?

My site is institutionalhistory.com if you’re interested 🙂