The smuggler’s return

5 February 1840

Charles Lewis Redwood stands at the helm, steering the St Leonard into the Yare. He remembers the tightening of his stomach the last time he watched Yarmouth coming into view, shackled with his men aboard the Admiralty cutter as his sloop, the Nancy, was towed into port.

Deftly, he slips the St Leonard up against the quay and oversees his men unloading her cargo. Honest fare, now, he carries between Harwich and London. Not like the bales of tea and barrels of brandy, stashed in the hulk, discovered when the excise officers intercepted the Nancy crossing the Yarmouth Roads, disguised as a fishing smack.

It’s four years since he was on this quay. The Harwich men were waiting outside the Gaol to greet the five smugglers from the Nancy after six-months imprisonment. Singing and slapping each other’s shoulders, they marched down to the dock and into the nearest tavern. He was impatient to return home but first he must treat the band of smugglers for supporting his men during their confinement with regular supplies of food and tobacco. It felt ungrateful to watch his friends supping their ale and not join them in a glass.

After all this time, he was glad to get the commission to come back to Yarmouth. At last he can call on the prison teacher he promised to visit. He seeks directions to Row 57. Will Miss Martin remember him?

She recognizes the sailor instantly, welcoming him into her little room. He’s taken aback by its bare simplicity. Brewing the tea strong, she manages to get two cups out of the teapot, made only for one.

It was a hard time, he tells her, when he left the Gaol. Fourteen months he spent, searching for honest work. With his wife and children to feed, it was a sore temptation not to go back to the contraband. But he stood by what his teacher taught him. Now, he says proudly, he is master of a respectable merchant’s ship.

The mariner’s eyes light up when she asks after his family. Sarah, his wife, has another baby on the way. William, his first-born, has become a sailor. He’s a strapping lad. Good and steady.

The teacher rummages through a box of envelopes, and takes out the letters of thanks from Edmund Cole and his wife, to read their cheery news. Like Redwood, the first mate had struggled when he returned home. But Cole had visited last summer and told Miss Martin how all the Nancy’s crew had finally left off smuggling. They are doing well, Charles Redwood nods. Fine men. He sees them often. The teacher is happy to hear him confirm Edmund Cole’s reports.

Shyly, before he leaves, the former prisoner takes from his sack two presents for the teacher. He bought them in France, a token of his gratitude for all she has done for him. He hopes she will like them. But sat on the table between them, the pretty vase and jewellery box look out of place, he thinks.

Once the master mariner bids her farewell, Sarah Martin opens the Liberated Prisoners book and writes of his visit and gifts—a vase covered in shells, and a curious glass box—his gratitude for what he thought his obligation to me. At the end of their confinement, she remembers smiling, the smugglers asked to speak with the prisoners, and begged them to listen to her advice, and treat her with respect.

She picks up the vase and box, and hesitates, weighing the strange trinkets in her hands.

I am not sure if she stands them on the mantelpiece or hides them away in a cupboard.[1]

***

The smugglers on the Nancy had been in prison before, as they told Sarah Martin. Why did her teaching touch them when previous correction had failed to deter their illegal activities?

In 1832 Charles Redwood was found in charge of the Union of Ipswich, sailing as a collier hauler with contraband concealed under the coal. His men were pressed into the Navy for five years—a gain for the Admiralty that won the services of experienced sailors, and for the Home Office that saved on the cost of imprisoning them. Of the six crew members, only the cabin boy was acquitted, as at the Yarmouth trial. But the captain must be made an example. Unable to afford the £100 fine, Redwood was sent to Springfield Gaol, a convict prison near Chelmsford.[2]

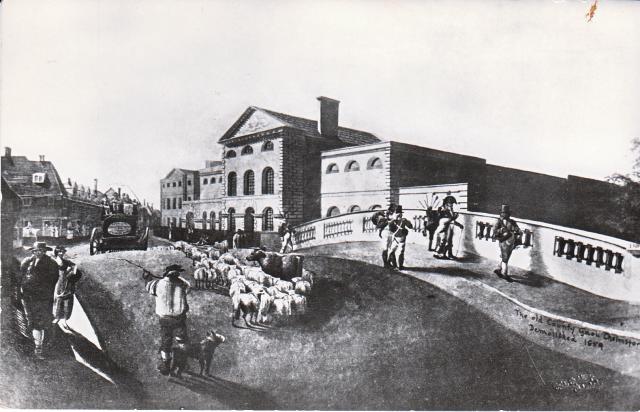

Springfield/Chelmsford Gaol (currently being researched by former prison officers)

Springfield opened in 1828 as a modern penitentiary, designed in the radial style to ensure close observation of inmates, with a treadwheel for hard labour. Under the silent system, inmates were prohibited from speaking with each other, on pain of punishment.[3]

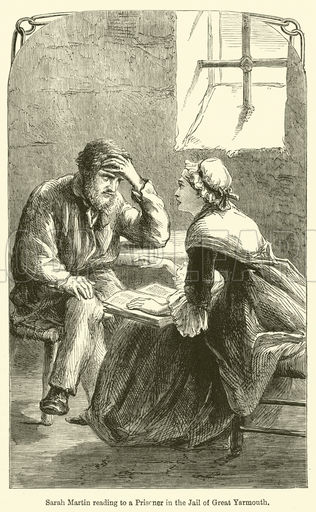

From Chatterbox, 1891

Housed together at Yarmouth Gaol and able to converse freely, the Nancy men laboured keenly at their lessons. While agreeing with the teacher that smuggling was a form of fraud involving habitual lying, they doubted they could afford to leave the trade. Discussing their concerns with Miss Martin, and mulling over the costs and benefits when she left, the five men began to embrace Christian reclamation as a group.

Mateship had bound the Nancy men together on the open seas. It sustained them in prison, with gifts from the smugglers’ band—one of the illicit friendly societies formed by contraband men. The vision of Christian fellowship, offered by the prison teacher, shared much in common with the values of fraternity and mutual obligation expressed by friendly societies across the trades, often symbolized in Christian terms, especially in the figures of the Good Samaritan and St Christopher.[4] They were embedded, too, in the sea-faring life where the maritime spirit of hardy independence was built on the interdependence of crewmen. Those same values girded the men in the difficult months after release, when the older ones kept a careful eye on their younger mates.

Determination to leave the smuggling trade was surely strengthened by the strain their imprisonment had placed on the men’s families and the fear of transportation if they were caught again. When Charles Redwood was arrested in 1836, his son Lewis was just two-years-old.

The census returns for the Redwood household suggest the precarious nature of sailoring life but also the principles of kinship and reciprocity that kept the master mariner on the straight-and-narrow and his family together. At each census the sailor and his wife lived at a different address but always in the streets by the harbour. In 1841, five of their eight sons and daughters, were with them in Castle Street. When the children left home, they remained close by.

All Redwood’s sons became mariners and his daughters married sailors or men employed in trades connected with the sea. In 1851 his widowed daughter Jane had returned to live with her parents, while she worked as a charwoman to support her young daughter and newborn son. By 1861, now remarried to another sailor, she was living next door to her mother Sarah, who was caring for two of her grandchildren.[5]

The former smuggler passed away in 1859, aged sixty-five. Proudly, his family or his friends placed notices in the Essex Standard and Chelmsford Chronicle, to note the death at Harwich of Mr Charles Redwood, mariner of that town.[6]

***

At the click of the latch, young Lewis runs squealing to the door and tugs at his father’s breeches. Sarah is all smiles. He feels the baby, firm in her belly, as he presses her in his arms. This one will not know his Daddy go to gaol.

Sitting in his chair by the hearth, he keeps an eye on the potatoes bubbling on the stove while his daughters set the table. Suddenly he is hungry as the herrings, bought today in Yarmouth, sizzle smoky-sweet on the griddle. Up on the mantelpiece, Sarah has added the vase to the collection of shell decorations, beloved by sailors, which her husband has brought back from his travels. The new jewellery box has pride of place, already containing her blue bead necklace and money for next week’s housekeeping. Its glinting glass casts flickering rays of lamplight onto the picture above. Cut out from a magazine, it’s his favourite print, A Sailor’s Family by Rowlandson.[7]

He turns away from the merry picture and looks at his own happy band, gathered around the table, his wife beckoning him. For a moment he thinks of Miss Martin, sat at the table in her spartan room, writing out verses for the prisoners to copy. Charles Redwood shakes his head and then joins the homecoming supper, beaming.

Thomas Rowlandson, ‘A Sailor’s Home’ (1787), Metropolitan Museum of Art, credit Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1833

***

And because everyone loves a sailor and I cannot access my pinterest account, here are more returning sailors (and some smugglers)…

A more raunchy Sailor’s Return by Rowlandson. Does the flitch of bacon suggest impending marriage?

More typical of Rowlandson and of bawdy style of many Sailor’s Returns

Compare and contrast…

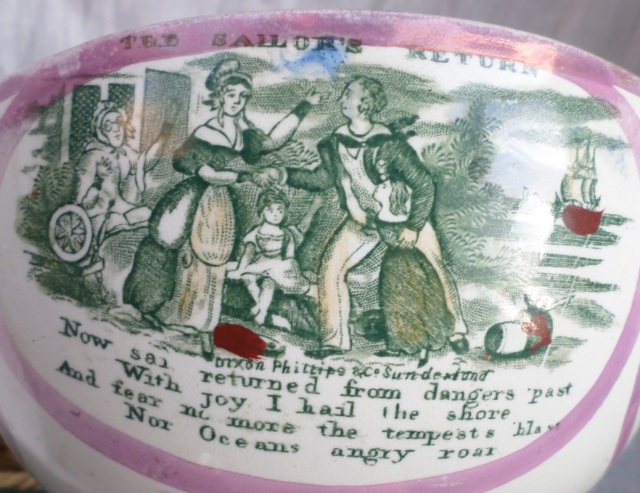

The Sailor’s Farewell and The Sailor’s Return were familiar motifs on pottery

And then there was The Smuggler’s Return…

The Smuggler at Home after a Successful Cruise, Henry Perlee Parker 1850

Smugglers Alarmed. Staffordshire Archives & Heritage

Fortunately, perhaps, I’ve lost the link to an extremely lewd and graphic set of Sailors Returns which I’m sure Charles Redwood did not display on his walls!

[1] Based on the following sources: Great Yarmouth Borough Gaol Committal and Discharge Book, Sept 1831-Dec 1838, Y/L 2/6, 18 May 1835; 1840 [258] Inspectors of Prisons of Great Britain II, Northern and Eastern District, Fifth Report, House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online (Proquest, 2005), 126–27 and 1839 [199], Inspectors of Prisons, Fourth Report, ibid, p. 172. Charles Edward Lewis was born April-June 1840: FreeBMD. England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 1837-1915 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Born in 1819, William was a sailor by 1841, living with his wife Mary on Church Street in Harwich, married to Mary: Class: HO107; Piece: 344; Book: 19; Civil Parish: St Nicholas; County: Essex; Enumeration District: 2; Folio: 29; Page: 17; Line: 19; GSU roll: 241380. Details of Edward Cole from the Liberated Prisoners Book are from 1839 [199] Inspectors of Prisons, 173–74. For further analysis of Redwood and other apparently reclaimed prisoners, see Helen Rogers, ‘Kindness and Reciprocity: Liberated Prisoners and Christian Charity in Early Nineteenth-Century England’, Journal of Social History 47.3 (Spring 2014): 721-45, doi: 10.1093/jsh/sht106.

[2] Essex Standard, 29 September 1832, p. 3.

[3] See extract from White’s Directory of Essex, 1848 at ww.historyhouse.co.uk/articles/prison.html, which also includes excerpts on the gaol from the Inspector’s Reports. Accessed 25 October 2016.

[4] Daniel Weinbren, ‘The Good Samaritan, Friendly Societies and the Gift Economy’, Social History, 31:3 (2006), pp. 319-336, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03071020600764464

[5] 1841 Census; Class: HO107; Piece: 344; Book: 20; Civil Parish: St Nicholas; County: Essex; Enumeration District: 4; Folio: 14; Page: 20; Line: 6; GSU roll: 241380; 1851 Census, HO 107/1760; 1861 Census, RG 9/1094; England & Wales, Free BMD Death Index: 1837–1915 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006.

[6] Essex Standard and Chelmsford Chronicle, 11 March 1859, both p. 3

[7] Thomas Rowlandson, ‘A Sailor’s Home’, etching from series Imitations of Modern Drawing (London, 1787), Metropolitan Museum of Art, credit Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933 http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/407353 . This illustration is a variant of the Sailor’s Return genre, itself part of a wider genre on the Labourer’s Return. Usually the homecoming sailor or worker is pictured at the threshold of the home, rather than in it, as here, reflecting longstanding ambivalence about the relationship between masculinity and domesticity. See Brian Maidment, ‘Domestic Ideology and its Industrial Enemies – The Title Pages of The Family Economist 1848-1850’ Christopher Parker, Gender Roles and Sexuality in Victorian Literature (Abingdon: Scholar Press, 1995), pp.25-56; Trev L. Broughton and Helen Rogers, ‘The Empire of the Father’, in Gender and Fatherhood in the Nineteenth Century (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007); and Joanne Begatio (Bailey), Parenting in England 1760-1830: Emotion, Identity, and Generation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Lovely — where did you find all those wonderful images!?

Hours on google Trev! This is a great site which allows you to search across all sorts of UK collections http://artuk.org @artukdotorg

Pingback: History, Imagination, and Invention | Storying the Past

Pingback: An Ex. Smuggler Returns to Yarmouth! – Norfolk Tales & Myths

Pingback: Great Yarmouth: The Smuggler’s Return! – Norfolk Tales & Myths