Convict Lads 1836-46: Friendship and Survival

This is a version of papers I gave at the European Social Science History Conference (Vienna 2014) and the British Crime Historians Symposium (Liverpool 2014). It explores what we can learn from multiple historical records about the friendship networks and survival strategies of boys and young men, transported to Van Diemen’s Land in the 1830s and 1840s.

My paper explores networks of offending and friendship in the survival strategies of young male offenders in the 1830s and 1840s. Their survival strategies were not, perhaps, terribly successful for all were transported, most after several imprisonments. I focus on 26 convicts transported to Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania. All were under 21 when first admitted to prison at Great Yarmouth, a seaport on the east coast of England.[1] They were typical of young offenders at the gaol, most of whom avoided transportation. Boys and young men (or lads as I call them) were the largest cohort of inmates and the most troublesome. Between 1839 and 1841, 41% of prisoners at Yarmouth were 18 or under. Two thirds of repeat offenders were under 21.[2] By reconstructing the social economies and networks of these lads, can we also, if tentatively, begin to get at their emotional economies?

The Tasmanian convict records provide a rich source for reconstructing the lives of offenders for, on arrival, they were quizzed about their offending histories, occupations and family connections.[3] Using access databases, I link this evidence with data from Yarmouth prison records, census returns and parish registers. In doing so, I’ve developed an approach I call ‘intimate reading’, combining qualitative and quantitative analysis to produce individual and group histories that illuminate each other. Rather than analysing large datasets from a distance, as in Franco Moretti’s ‘distant reading’ method, intimate reading means getting ‘up close and personal’ with individuals and locating them in their affective, neighbourhood and occupational networks.[4] Social profiling of this kind exposes patterns in employment, family and social ties that are not so readily apparent when reading fragmentary evidence of individual lives.

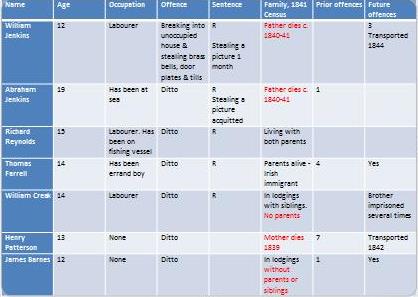

To illustrate intimate reading, I’ll move between one individual – William Jenkins – and the wider cohort. William was sentenced to seven years transportation in 1844, aged about 17, with two other Yarmouth boys.[5] They typify the convict lads whose average age when first imprisoned was fifteen-and-a-half.[6] On average, these convicts had served 5.5 imprisonments prior to transportation, mostly before they were 21.[7] Two-thirds of their committals were for petty theft.[8]

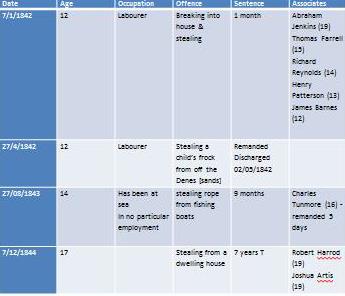

My starting point for reconstructing the boys’ histories is the papers of the Christian prison visitor Sarah Martin who, between 1818 and 1843, taught inmates at the Gaol and followed their progress after departure.[9] Her notes on the character and conduct of inmates, during and after release, offer tantalising glimpses into the lives, associations, and even feelings of her prison students, though refracted through her pious and disciplining gaze. As you can see from her notes on the two Jenkins brothers, William was around twelve when first imprisoned in 1842 for stealing. She found him ‘Remarkably quick in natural ability and clever but refractory, fearless and illdisposed’ [sic].[10]

Sarah Martin’s notes on Abraham Jenkins, following his first imprisonment, from the Fifth Report of the Prison Inspectors (1840), p. 125.

In 1839 William’s elder brother Abraham had served three months in which time he learned to read and write.[11] The teacher supported him on release but feared ‘his parents will not exercise a good influence over him’.[12] She revised her opinion of the boy’s father, comforting him through illness and was at his bedside when he died. ‘This holy and good man was a Tinker’, she noted, ‘with a large family in the deepest poverty’.[13]

![‘The Believer’s Death’, Selections from the Poetical Remains of the Late Miss Sarah Martin of Great Yarmouth (Yarmouth: James M. Denew, n.d. [1845]), pp. 60-1.](https://convictionblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/image.jpg?w=640&h=478)

‘The Believer’s Death’, Selections from the Poetical Remains of the Late Miss Sarah Martin of Great Yarmouth (Yarmouth: James M. Denew, n.d. [1845]), pp. 60-1.

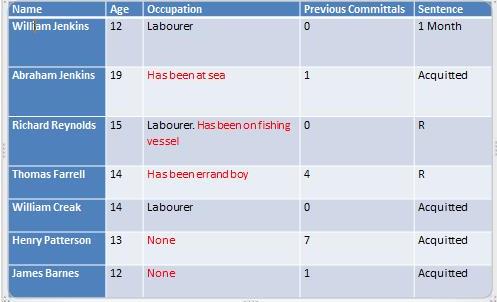

William & his mates: 7 January 1842, Breaking into unoccupied house & stealing brass bells, door plates & tills

As you can see from the profiles of the six boys arrested with William, most if not all were without work or in between jobs. None of the convict lads were in school when they first began offending and many had yet to enter full-time work, though about a third served some kind of apprenticeship. However, when we try to locate William’s mates in the 1841 Census, we find that only one was at home with his parents and perhaps as many as 4 had lost one or both parents. Two-thirds of the convict lads had lost a parent, often shortly before their offending began.[15] 55% had lost their father, the chief breadwinner, while a fifth had no surviving parents. Their family support networks, then, were acutely compromised. Nearly a third were convicted as rogues and vagabonds, some of whom had been homeless or in the workhouse.[16] When William was released from gaol at the end of his first imprisonment he was handed over to the parish relieving officer.[17]

Some families were unable or unwilling to accommodate a son who failed to bring in regular income or brought shame on the household. Robert Harrod, transported with William, was just twelve when dragged before the magistrates by his mother for wandering from home.[18] He was one of 5 convicts prosecuted by a relative; one measure of the strain on these families. Juvenile friendships, therefore, were crucial for these boys as they sought entry into the adult world of male labour and companionship. Searching for employment on the peripheries of the labour market, work, play and offending segued into each other. In Van Diemen’s Land, William attributed his nine month prison sentence not to stealing rope (as he was convicted) but to ‘setting boats adrift’: was this scavenging, pilfering, play or a mix of all three?[19]

While all but one of the convict lads had stood trial alone, a third of their prosecutions were for joint-offending and probably an even greater proportion of their offending took place in groups.[20] Some knew each other through work, as no doubt did the boatmen Lewis Goodwin and John Bowles, convicted of stealing a horse, but many met or firmed up acquaintances in prison.[21] Their friendships and rivalries can be traced through their gaol admissions and disciplinary offences inside.

Detail from ‘Sarah Martin the Jail Missionary’ in Women of Worth: A Book for Girls (London: James Hogg, 1859), p. 58

Lacking control in the outside world, William Jenkins asserted himself in prison, notching up eighteen punishments, far more than most prisoners accumulated. His refractions were associated with boisterous spirits and staking his place in the inmate pecking order; fourteen punishments were for larking about, being noisy or jostling with other boys.[22]

We see here the significance to boys of the fierce alliances within their own peer group rather than the influence of older, hardened associates that preoccupied commentators and policy makers. The boys could disturb and anger older inmates as well as the gaoler, chaplain and prison visitor whose authority they challenged. On one occasion, adult prisoners complained the incessant noise between William and another boy prevented them from reading.[23]

Acting up, throwing their weight around, filling the prison with their voices enabled the boys to control their environment while demonstrating the toughness expected of men in the heavy and often dangerous occupations of the sea-faring port. Larking about and tests of daring, in and outside the gaol, were among the ways that they gained entry into the convivial world of male labour, sport and pleasure. We can detect the boys’ initiation into the rituals of adult masculinity in the tattoos worn by at 23 of the convict lads when they arrived in Van Diemen’s Land, though it is likely all were decorated.[24] Their tattoos depict how they – rather than others – viewed themselves, their passions and close connections. Probably most had begun adorning themselves long before they left Yarmouth and their show how important style and appearance were to boys in the port. Eight convict lads wore tattooed rings. The one Robert Harrod wore aged twelve, no doubt marked his entry into the circle of night-time friends with whom he stayed away from home. William Jenkins was among a group of boys discovered by the gaoler apparently experimenting in tattooing by pricking a piece of bread.[25] Needles and ink for the purpose could be purloined from the prison visitor from whom, on occasion at least, William had stolen needles.[26]

William’s ‘Marks’: Marks: Anchor & cable mans head Sun W on right arm below elbow H.L. Anchor and cable H.L boat with man row dots and large scar & 2 small dots on left arm below the elbow L H on back of left hand 5 dots between forefinger & thumb. Ring on 2nd finger left hand, small scar on right eye brow

Most boys began tattooing themselves with letters or the dots which then, as now, signaled friendship groups. 16 lads sported dots, including William with a row of dots on one arm and five dots between forefinger and thumb. Initials and names were the commonest form of tattoo, often combined with a figure of the person they name. Seventeen of the convict lads had tattooed their own name or initials. William’s initial was next to the head of the man (perhaps his father or the man he hoped to become). The man’s face was illuminated by the sun, shining above him, and placed next to the anchor and cable, maritime signs of faith and safe passage.

Thirteen lads included the names or initials of friends or relatives. HL was a significant other for William – either a love-attachment or a friend – for the initials were repeated three times. Initials most commonly represented self, lovers and family, indicating the strength of these attachments despite the highly compromised circumstances of the boys’ familial networks. One boy, prosecuted by his parents for stealing from his mother, portrayed all his family, including his father smoking and drinking, and two men ‘arm in arm’, probably the brother with whom he was transported.[27] Six lads had depicted at least one male figure in their tattoos, and six at least one female figure.

Growing up in a town dominated by the sea with its dangerous occupations, the boys used their tattoos to warn off fate and to bring good luck. Ten bore combinations of sun, moon and stars; seven had hearts and darts. Thirteen lads sported the anchor, while eight had embellished a mermaid. Maritime insignia depicted the sea-faring trades many aspired to join. Though two-thirds of the convict lads had yet to enter a trade when they left Yarmouth, only six described themselves as ‘labourers’ in Van Diemen’s Land. Many claimed instead their father’s occupation, in whose steps they had hoped to follow, or in William’s case his elder brother. He claimed to be a seaman, just like Abraham and the ‘boat with man’ in his tattoos.[28]

John Newstead’s tattoos, described by Gaoler, 8 June 1844, showing the names of his mates and crossed pipes and glasses of friendship. He was transported in 1848. John Newstead, 21025, per Ratcliffe (2), 1848, CON33/1/91

By intimately reading a complex ‘body of evidence’ drawn from a multitude of sources we can begin to interpret the social and even the subjective experience of boys and young men, cast by contemporary discourse as ‘artful dodgers’ and ‘idle rogues’. Juvenile offences closely correlated with the place of boys on the peripheries of the port’s casual labour market and opportunities it afforded for unsupervised recreation and petty theft. Most convict lads had experienced parental loss, poverty, and sometimes family conflict. Peer groups formed as supplements and alternatives to kinship ties and were cemented by male camaraderie and rivalries played out in the streets and prison wards. In their body adornment, the boys celebrated and commemorated their attachment and loyalty to family and friends, their town and its way of life.

[1] A similar number were transported elsewhere following conviction at Yarmouth, along with much smaller numbers of women and older men.

[2] Based on analysis of the Great Yarmouth Gaol Registers for three years 1839-41. The Gaol records are held by Norfolk Record Office.

[3] Most of the Van Diemen’s Land records are held at the Archives of Tasmania, Hobart, and many are searchable online at http://portal.archives.tas.gov.au/menu.aspx?search=11, including the conduct records and convict indents which contain considerable detail on individual convicts. Partial transcriptions of the conduct records are searchable at Founders and Survivors: Australian Life Courses in Historical Context, 1803-1920, http://foundersandsurvivors.org/.

[4] Franco Moretti, Graphs, Maps and Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary Theory (London: Verso, 2005).

[5] All three were tried at Norwich at the Norfolk Special Assizes, 17 December 1844 for stealing money from a dwelling house: William Jenkins, 15933, per Theresa, CON33/1/67, CON14/1/29, Description List, CON18/1/44; Joshua Artis, 15826, per Theresa, 1845, CON33/1/67, CON14/1/29, Description List, CON18/1/44; Robert Harrod, 15914, per Theresa, 1845, CON33/1/67, CON14/1/29, Description List, CON18/1/44.

[6] The youngest was just shy of twelve-years-old when summarily convicted as a rogue and vagabond, intent on stealing. Gaol Register, 26 May 1841. The Gaoler entered Isaac Riches age as 14. Almost certainly this is wrong. Dates of christenings, where they are available, are the best guide to birthdates before compulsory birth registrations were introduced in 1837 since children were usually baptised within days of their birth. Isaac was baptised 13 June 1829 which suggests he was 11 when he entered prison. This birthdate correlates with the age (17) he gave on arrival in Van Diemen’s Land. See ‘1813 to 1880 Baptism Project Great Yarmouth St Nicholas’ http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~tinstaafl/Church_Pages/yarmouth_gt_1829.htm#Top; and Isaac Riches, 17982, per Joseph Somes (1), 1846, CON33/1/77, CON14/1/35, Description List, CON18/1/45.

[7] Their combined admissions to Great Yarmouth Gaol prior to transportation total 143. In 122 of these committals (85%), they were under 2.

[8] About 100 of their 143 committals at Great Yarmouth involved some kind of theft.

[9] Sarah Martin’s surviving ‘Everyday Books’ are held by Great Yarmouth Museum Service and are displayed at the Tolhouse Museum, formerly the gaol.

[10] Sarah Martin’s prisoner register, 1842, no. 120, in ‘Successive Names’ Book, Great Yarmouth Museums.

[11] Gaol Register, 24 May 1839. Abraham was convicted with stealing rope from the lugger Ann, along with Joshua Artis who would be transported with William.

[12] ‘A.J.’ in Martin’s table, ‘A Glance at Some Persons who seemed after their Imprisonment to have been Reclaimed or Improved’, 1840 [258] Inspectors of Prisons of Great Britain II, Northern and Eastern District, Fifth Report, House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online (2005), 128-29.

[13] [Sarah Martin], ‘The Believer’s Death’, Selections from the Poetical Remains of the Late Miss Sarah Martin of Great Yarmouth (Yarmouth: James M. Denew, n.d. [1845]), pp. 60-1.

[14] Elizabeth Jenkins and her children were removed to Aylesburton, parish of Lydney Gloucester, 14 April 1840: Index of Examined Paupers, 1756-1844, Norfolk Record Office, Y/L16/8, mf/RO 597/6.

[15] 55% had lost their father; 39% their mother. Only a third had a surviving parent.

[16] Three had convictions for being refractory paupers.

[17] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 14 April 1842.

[18] Great Yarmouth Borough Gaol Register, 26 September 1837. Henry Coppin, the youngest to be sentenced to transportation was fourteen for stealing an oil frock and trousers from a ship while he was homeless, following his father’s transportation. See Gaol Register, 28 October 1841 and Henry Coppin, 11429, per Anson, 1844, CON33/1/49, CON14/1/25, Appropriation List, CON27/1/10, Description List, CON18/1/41. William Copping was sentenced to 7 years transportation 29 December 1840. William Copping, 3589, per Barossa (1), 1842, CON33/1/16, CON14/1/12, Appropriation List, CON27/1/9, Description List, CON18/1/30, p. 35.

[19] Gaol Register, 27 August 1843 (9 months for stealing rope from a ship); ‘Setting boats adrift’ – Statement of Offence – in Conduct Record, CON33/1/67.

[20] 48 out of 143.

[21] John Bowles, 2635, per Blenheim (1), 1837, CON31/1/3, Appropriation List, CON27/1/7; Lewis Goodwin, 1264, per Blenheim (1), 1837, CON31/1/16, Appropriation List, CON27/1/7.

[22] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, Jan 1841-Dec 1845 (Norfolk PRO Y/L2 48)

[23] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 11 November 1842.

[24] The penal authorities see to have consistently transcribed tattoos after 1840, so there are no descriptions for John Bowles or Lewis Goodwin. Yarmouth’s Gaol’s Index and Receiving Book reveals Thomas Tripp was tattooed with 3 blue dots on his left hand (30 April 1839) but his marks are not recorded in his convict documents: Thomas Tripp, 12997, per Lady Franklin, 1844, CON33/1/55, p. 12997, CON17/1/1, p. 16, Appropriation List, CON27/1/10, CON18/1/31, p. 303, To NSW per Mangles. To Norfolk Island 1840.

[25] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 11 May 1844.

[26] Gaol Keeper’s Journal, 28 March 1842.

[27] Isaac Riches, 17982, per Joseph Somes (1), 1846, CON33/1/77, CON14/1/35, Description List, CON18/1/45; Christopher Riches, 17981, per Joseph Somes (1), 1846, CON33/1/77, CON14/1/35, Description List, CON18/1/45.

[28] William Jenkins, 15933, per Theresa, CON33/1/67.

Helen: have you ever managed to trace any of these ‘lads’ back from van Diemen’s Land and looked at their long-term histories. Do they remain ‘deviant’. You mention the importance of family break-up, death and stress. Does the subsequent history of these lads show that all links with their birth family tended to be broken permanently?

Hello John. Yes I have searched for their future histories and hope to write about these at some point. Most got into some trouble during their time as convicts but it was nigh on impossible getting through probation without a mark against your name. Some got into a cycle of insubordination and punishment and considerable numbers had their sentence extended – again common. But only a very small number were convicted of an offence after their sentence had ended. Unless they got into lots of trouble with the law – or have intrepid genealogists among their descendants – it’s quite hard finding much after their sentences ended other than info on marriages, children etc from parish registers in Van Diemen’s Land. Most of them came out of their sentences in time for the Gold Rush so hopped it over to NSW. None found their fortune there and many soon went back to VDL and stayed in working-class occupations. A few got washed up and ended their lives in pauper institutions, as did many convict men who didn’t manage to marry and settle. I know of a very small number of convicts who made it back to UK and at least one who was thought to have brought his wife and children out to VDL, but I suspect in majority of cases they never saw families again and some will have lost all contact. I found one letter from a brother sent to authorities years after lad had been transporting, saying their mother had died. On the whole, I’d say most ceased being ‘deviant’, having been pretty small-time in the first place, though know doubt like those left behind in Yarmouth, there was a fair bid of ducking and diving and muddling through! Thanks for the questions. They make me want to go back to my databases! Helen

One of my husband’s ancestors, Moses Percival, was transported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1831 on the ‘Larkins’ for stealing barley and a sack (in that order!). It was fantastic to find a description of him amongst Tasmania’s records.

Thinking about John Herson’s comment above – there was a link kept with his family at home (wife and 3 children) and one wonders whether they might have joined him at some point in the future, as he’d earned his freedom ticket and established a business when he sadly died in 1839 in an accident. His former employer (and perhaps mentor) ensured that the value of his estate (a parcel of land worth around £200-£300) was bequeathed to his wife back in Essex.

Thank you for sharing your sad and moving story about Moses. I suspect that married men were more likely to stay in touch with their family in the UK. Maintaining the link will have been a struggle for many. I’m hoping this blog will help me get in touch with descendants who might be able to help me trace what happened after their sentences. It’s great having the Tasmanian records free online. Such a terrific resource. I too have a convict sentenced for stealing a sack of barley!

Truly fascinating post. One of the men on board RMS Tayleur (the so-called ‘Victorian Titanic’, which sank on its way to the Australian Gold Rush in early 1854) was an ex-convict sent from Stamford, Lincolnshire, to Van Diemen’s Land for a second offence of sheep slaughtering (I think the first offence was stealing a horse as a teenager, if I remember right) with an older friend. They’d been on their way home from the local pub, where they’d been celebrating Samuel Carby (Tayleur passenger)’s upcoming wedding when they came across a sheep in a field, slaughtered it, and clumsily butchered some mutton which they then took home. They were lucky to be sentenced to transportation for 10 years as a few years prior they would have been hanged. Samuel ‘made good’ and received a pardon while working for the man who went on to become the first premier there, became a free man in time for the Australian Gold Rush, made a fortune and returned to Lincolnshire for his fiancée and now-grown son, then persuaded them to return to Australia – this time with a cargo of shoes to sell to fellow immigrants – on the most luxurious ship of the time, the White Star Line’s RMS Tayleur. His English descendants recently found out that some of his mail remains uncollected in Australia and are in the process of tracking it down, which is tremendously exciting. I would recommend anyone with ancestors living in Australia/Tasmania at the time you refer to in your post to check Trove for mention of them and especially of mail waiting for them as it could still be there somewhere. Samuel Carby was a hero who survived the Tayleur and rescued others, a man who redeemed himself repeatedly over the years post-transportation. His friend (who had tattoos including personal initials like you mention above) had a more common name – George Bell – and it’s less clear what happened to him next. If anyone has further information on either of them I’d appreciate them getting in touch 🙂

Thank you for your fascinating comment Gill! I am now going to order a copy of your book. None of my lads made it big in the gold fields though most tried their hand! The Trove newspapers have been a great way for me to find out bits and bobs on my lads after they gained their freedom – and the shipping records. I’ve concentrated on convicts sent to VDL precisely because of the richness and online availability of so many of the Tasmanian records. Look forward to reading your book! Helen

Hi Helen,

I’m the great great grand daughter of William on my mothers side, Sadly she passed away recently but would’ve loved to read what you have written. You probably have already found that he had 9 children, one of which is John Walter Harold Jenkins. He had four children to his first wife. Mary. Thomas Early Jenkins my Grandfather .My mother was the baby of the family Pauline Jean Jenkins. Mum told me The Jenkins family stayed in the surrounds of Hamilton where William settled. My grandfather Thomas raised five children in that area and they all considered it to be home. And mum always felt the happiest at the Lake country as us locals call it. I have done a fair bit of the family tree over the years.

Thanks again for the truly wonderful insight into Williams life

Gaylene Jones

Hi Gaylene

How lovely to hear from you and that my blog gave you insights into William’s early life. Since writing the blog I managed to identify William and his family at Hamilton because he placed an ad in the Hobart paper to try and find his brothers. It seems they were probably trying to join him. I only managed to do this because of the wonderful Trove archive which has digitised Australia’s historical newspapers.

Here’s link to draft of my chapter on William in a forthcoming book. The first part is about ways of doing historical research so you may just want to skip to where I start talking about William. I so enjoyed writing about him. I’ve run into a wall on Abraham and Edward but hope something will turn up. I’m writing a book about Sarah Martin who taught prisoners and what happened to them and their families afterwards. If you know anymore about William’s life in Hamilton and his family, I’d love to hear about it.

This is the chapter https://www.academia.edu/20792006/Making_their_Mark_Young_Offenders_Life_Histories_and_Social_Networks_in_True_Crime_Histories_Micro-Studies_in_Law_Crime_and_Deviance_since_1700_edited_by_Anne-Marie_Kilday_and_David_Nash_Bloomsbury_forthcoming_2016_

And this is another blog on William which has some other images https://manyheadedmonster.wordpress.com/2015/08/07/captured-voices-2/

Sorry to hear about your much loved mother and good luck with searching your family history.

Thank you so much for getting in touch. Helen

Pingback: History A'la Carte 12-11-14 - Random Bits of Fascination

Pingback: The Real Artful Dodger?

Pingback: The REAL Artful Dodger? | Prison Voices of the Condemned

Pingback: Artful Dodgers and Children of the Dock – Prison Voices